OSH Housemasters

- Dallas Wynne Willson (1905-1920)

- Rev. Frank Field (1920-1930)

- Arthur Gamble (1930-1941)

- Eric Kelly (1941-1956)

- Paul Colombe (1956-1971)

- Peter Corran (1971- 1986)

- Norman Semple (1986 -1993)

History

The Story of an Old School House

Sir John Gresham’s Grammar School was founded following the suppression of an Augustan Priory in 1539 which had run a School at which he and his brothers were thought to have been educated. Letters patent were drawn up on 27th April 1555, and work on the schoolhouse had begun before the granting of the first patent. The Gresham family were originally from the village of that name but had moved to Holt by the end of the fifteenth century. Sir John purchased the family’s ancestral manor house from his brother in 1546 for £170 for the purpose of converting it into a School. Sir John was a member of the Mercers’ Company, but in 1552 was enrolled as a benefactor of the Fishmongers’, and it was to this Worshipful Company that he entrusted his new School in 1556. Sadly, Sir John was never to see his wish fulfilled as he died of the plague seven days later.

The Fishmongers’ were unable to carry out their trust until 1562 when the School was opened. The earliest surviving statutes for governance of the School were drawn up by Dr Thomas Gale. In these we learn that the master’s salary for teaching classes to the thirty free Sir John Gresham scholars was £20. This was augmented by the use of six acres of land and the garden and outbuildings behind the schoolhouse. The master could also take as many boarders and paying or ‘pensioner’ scholars as he wished. The schoolhouse door was opened at 6am, lessons began after prayers at 7, continuing until 11 and resuming between 1 and 5. Prayers for the founder and the governors were said before dismissal, and some boys were delegated to sweep the building and close the doors at 6pm. Lessons finished at 3pm on Saturdays. On Sundays the pupils sat together in the School pew in the Parish Church. The Statutes dictated that the master was to abstain from alehouses and all unlawful games. A scholar could be punished for coming to School with ‘head uncombed, his hands and face unwashed, his nose or shoes uncleanly, apparel torn or not well girt unto him.’

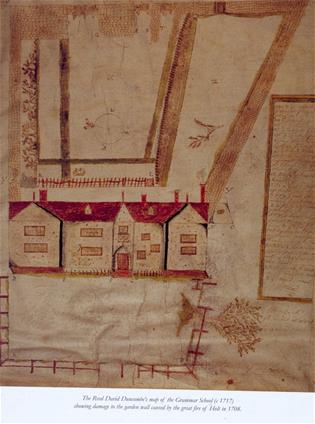

When Richard Snoden became master in 1602, however, he did not find the School in a very good state, and when Thomas Tallis arrived in 1606 there were no pupils left at all. Tallis set about making improvements, obtaining an allowance for the salary of an usher(assistant), as well as expanding the library, and managed to send at least 25 boys to Cambridge during his tenure. Legend has it that during the Civil War a small attempt at a Royalist uprising in Holt led to usher Thomas Cooper being hanged in front of the schoolhouse door, but records show that he was actually executed in Norwich. In 1708 ‘A sudden and lamentable fire’ burnt down almost the whole town of Holt in the space of three hours. Fire lapped at the walls and garden of the School, making several breaches, burning the stables, barn and outhouses but sparing the house itself. Rev Duncombe, master following the fire, had the task of repairing the damage and produced a hand-drawn map showing the details.

Halcyon days

An advertisement from John Holmes’ 1735 Greek Grammar reads “At Holt in Norfolk, in a large commodious house, pleasantly situated, young gentleman are boarded and completely qualified for all manner of business in Latin, Greek, Arithmetick in all its parts … by the author and proper assistant.” Under Holmes the 1730s were halcyon days for the School, it gained an excellent reputation locally, drawing pupils from all sections of society including gentry, farmers and tradesmen. There were often 70 pupils, 30 free scholars, the rest paying. Holmes was the first master not in holy orders, and broadened the curriculum to include subjects such as history and geography. By 1740 a School play had been adopted, being performed at the breaking up for the summer holidays. Holmes has been described as “one of the greatest of all the headmasters in the four hundred years of the School’s history.”

When Rev B Pullan was appointed master in 1808 there was only one other School in Holt, but by the time he retired in 1858 competition had increased considerably, with a National School, a freechurch British School and a day Grammar School. It soon became evident that reform was necessary for survival, and Pullan’s improvements included the addition of navigation, mathematics and land surveying to the classics. In 1852 the ‘visitors’ or inspectors complained of the lack of a playground attached to the School, noting that pupils played in the streets and mixed with boys of lower classes, and that respectable parents had begun removing their sons. By 1857, with Pullan aged 69, the School was in decline and the visitors were suggesting the need for a new building and younger staff.

The refounding

The governors were asked to rebuild the schoolroom and build a house for the master to house twenty boarders. The estimate was considerable, and the Fishmongers’ had to take out a thirty year mortgage for the project which took place in two parts between 1857 and 1860. The new schoolroom, built onto the side of the Elizabethan structure, was designed by Richard Suter of London and built by Mr Orman of Ipswich. Light and ventilation had been carefully considered, and the room could be divided in two with folding doors to accommodate different classes. At the end of the room were bookcases for the library, and outside was a spacious playground. It was twice the size of the original classroom and had provision for more dormitories above if needed.

At the grand reopening ceremony in November 1858 the Prime Warden of the Fishmongers’ Company introduced the new master Rev Charles Elton and said that the revived statues were intended to restore the School to the high standards intended by the founder. After a service in Holt Church, 100 guests assembled in the beautifully festooned schoolroom for a sumptuous lunch, speeches and music. Rev C Elton spoke of the ‘scheme of liberal and generous instruction’ he intended to pursue. French and drawing were soon introduced, a cricket field laid out, and fives and tennis courts built. Forty boys practised drill under a rifle corps sergeant. The new master was known for his severity and ruled with the cane.

The new statutes set out provision for fifty free scholars from Holt and the neighbourhood to receive instruction in reading, writing, arithmetic, English grammar, history, geography, Latin, mathematics, geometry and Greek. Holidays were given at Easter, Midsummer, Michaelmas and Christmas. Visitors examined the scholars twice a year to ensure standards were maintained, and the master’s appointment was biennial. Prizes were provided for exceptional pupils and exhibitions awarded to assist with university education.

A pen portrait of Elton’s successor in 1867, Rev B Roberts, describes him as ‘tall, portly and whiskered’, and says that he used the cane rarely and temperately. He presided over the big noisy schoolroom with seniors facing him in rows of iron desks working on slates, and younger pupils seated on benches around the room receiving different tuition. In 1875 an additional master was appointed to teach English and writing and new classrooms called the ‘Tin Tabernacle’ were put up on the field. A building behind the schoolhouse, known as Church House, was run as a boarding house by Miss Jackson, and housed the usher, a French master plus fifteen boys. It was well run but lacked a good water supply, and when one resident died of Typhoid fever in 1886 it was closed down and demolished.

In the 1870s an annual athletics day was introduced with prizes, and there was a flourishing football club. In 1890 the visitors found Roberts ‘worthy of especial commendation’ and the examination results excellent. Education was changing, however, and the Endowed Schools Act meant a new scheme was necessary. Various options were considered by the governors but establishing a Public School on similar lines to Uppingham and Repton was favoured and Rev B Roberts retired with a generous pension in 1900. Plans were drawn up for a new School on the present Cromer Road site by the Fishmongers’ surveyor Mr Chatfeild Clarke with provision for 280 pupils plus ample space for future expansion, and a new headmaster was sought to take the School into the twentieth century.

Old School House group c. 1897

The Junior House 1900-1936

When newly appointed headmaster George Howson arrived in 1900 he found that the new buildings on Cromer Road were not ready for occupation so he set up home at the Old School House with a handful of senior boys, supported by his sisters Rosa and Mary who acted as housemistress and matron. When his own house (Howson’s) was ready in 1903, the headmaster left OSH in the capable hands of J.R. Eccles. Owing to increasing numbers, however, Eccles had to board boys at the Weybourne Springs Hotel from May to July while additional accommodation was added. JRE, as he was known, was a confirmed bachelor who lived and breathed for the School. He knew all the boys’ names and was especially kind to the new ones. He could also be extremely fussy and precise, however, once purposefully striding out to bat at 5.59 for a cricket match that was due to end at 6pm.

In 1905 OSH became officially known as the Junior House under its founder Dallas Wynne Willson. The Gresham reported “Of course we took a little time to settle down, but we are learning now to be orderly, tidy and punctual.” Football skills were said to be improving, with players learning to talk less and play more, and residents were enjoying excellent health. The only epidemics reported were of different types of games such as ‘Red Indian warfare’ and the magazine summed up, “we think we are in all respects a very Happy Family.”

Wynne Willson, known affectionately to the boys as ‘Bags’, married on 18th July and returned from honeymoon to furnish and make ready his new boarding house. He started with 30 to 40 boys under fourteen, the two lower forms being mainly taught at OSH but going to the Senior School for Chapel and special lessons. The house was well served for playing fields, with twelve acres for cricket and football, and large gardens kept the kitchen well supplied with fruit and veg. A young gardener/handyman called Stanley was kept busy cleaning the boys’ boots & shoes, as well as fetching luggage from the station, whilst a cook and eight or nine maids took care of the house and its residents. After a year or so a matron, Ada Newcombe, was appointed. Nicknamed ‘The Newe’ or ‘The Newk’, she worked hard and exerted an excellent influence over the boys.

Kindly, but quick tempered, Wynne Willson maintained high standards of honour in the house. Boys would sometimes try to wind him up by talking pigeon French in his language lessons, but his punishments were never severe, usually consisting of ‘no jam for tea!’ Matron, on the other hand, was said to have the deportment of a sergeant major, and ran the house in a strict and practical manner. Boys respected and by no means disliked her, but turnout for story reading evenings in her room was rather poor. In the autumn term of 1907 matron had a crisis to deal with in the shape of an outbreak of Diphtheria. Dr Gillam advised that residents be moved out, and boys stayed in two houses in Sheringham, enjoying playing hockey on the beach in the afternoons. OSH was inspected and a combination of gas leaks, poor ventilation and overcrowding discovered. Numbers were reduced to 28 and a new wing built to improve living conditions, consisting of two large dormitories, classrooms, changing rooms, etc.

In his memoirs Wynne Willson recalls a story from the early days of the boarding house when a small boy was found by a maid one morning wrapped in a dust sheet in a passageway. The poor little chap had got up in the night, and having lost his way back to his dorm, simply curled up on the floor amongst the luggage. Realising he was very cold, the kindly maid put him to bed with a hot water bottle. The same new boy, very nervous when asked his place of birth(Regents Park) answered ‘Please sir, in the Zoo’, only to be rewarded with howls of laughter from his classmates. The housemaster was soon blessed with twin girls who appear in all the house photographs and were a source of great interest amongst the residents and even the headmaster. They had many friends amongst staff children and enjoyed a very happy childhood with their brother amidst the spacious surroundings of OSH and the wider countryside.

OSH in wartime

In 1914 the peace was shattered by the outbreak of war. Rumours had started in July, and when news was posted outside Rounce & Wortley’s stationery shop there was an outburst of cheering. In August Captain Miller organised a meeting to help the wounded, forming a committee and obtaining permission to use the dormitories as a temporary hospital if necessary. Red Cross lectures on first aid took place in the OSH gym and a detachment of motor cyclists from Brighton took up residence there, followed by a battalion of Sussex Territorials. These were the forerunners of large numbers of soldiers to be garrisoned in Holt for the duration owing to fears of invasion along the north Norfolk coast. Wynne Willson became a special constable, patrolling the streets at night, checking bridges for explosives and helping to enforce the blackout. The first zeppelin raid took place in January of 1915; the first bombs to fall on English soil. The little boys of OSH were on the whole more excited than alarmed and eagerly explored craters left by bombs in the Glaven valley the next day, although some had to be gathered together around the fire and read stories to stop their tears.

Rumours of spies and airships were commonplace, and the housemaster was told to be prepared to evacuate his house at short notice. Boys were instructed to have their bicycles at the ready and to go west on side roads towards Kings Lynn. When ordinary games were not possible, boys were formed into troupes of scouts and taken on exercises. Feeding became more of a problem, and boys were put on their honour not to eat more than 4 and a half slices of bread per day. Water had to be used sparingly, and the boys helped by avoiding their daily cold showers where possible. Services were held weekly in Chapel to remember OGs who had been lost as the list was growing all the time. On Armistice Day a service was held in the afternoon followed by a procession of soldiers through the streets of Holt. A public dinner was held in July 1919 to welcome home returning soldiers at which Wynne Willson made a speech. He was later to commission of touching tribute to the boys of the junior house who lost their lives in the form of a vellum memorial complete with a photograph of each pupil as he remembered them aged 13 or 14.

OSH in the 20s

At Wynne Willson’s retirement in 1920 the post was taken over by the Rev Frank Field whose own retirement notice in 1930 highlighted his ‘wise thoughtfulness’ and wide influence as both chaplain and housemaster in his 25 years at the School. Owing to his rather forbidding, bird-like appearance he was known affectionately as ‘Beak’, but was always ready to join in the fun at house parties. He took a great interest in the activities of the house and always gave sports teams a rousing pep talk before their matches. Sometimes appearing somewhat distracted and absentminded, he could put on a ‘raging lion’ act if roused, and once roared “You blue blooded aristocrats” at some boys who had upset the kitchen staff by referring to them disrespectfully as ‘skivvies’. Rev Field had four sons and two daughters, and his capable but happy-go-lucky wife acted as matron.

Uniform for the 50 junior boys consisted of a blue blazer with brass buttons and crest on pocket, grey trousers, black shoes, white shirt and grey house tie, plus cap with badge. Gerald Holtom, who became a day boy in the junior house in 1922, remembered that “Boys at the OSH had the exceptional advantage of being taught by senior school staff and the added advantage of being encouraged to use senior school facilities …” He recalled cycling to Big School for special assemblies, lectures and choir practice, and assembling on the parade ground on Sunday mornings for the two-by-two march to Chapel. Boys would go for long walks in the afternoon, exploring fossils on the Cromer Bed, searching for amber on the beach, or bird watching at Blakeney Point.

The Gamble years

Captain of OSH J.F.P. Skrimshire remembered returning in September of 1930 full of curiosity and some misgivings following the ‘Beak’s last term. Their new housemaster Arthur Gamble soon provided a warm welcome and the necessary reassurances. He was by no means a stranger to the boys, having thrilled them in history lessons with bloodier episodes and entertained them with his ready wit in Latin. Although some prefect privileges were abolished, Skrimshire says, “our comfort was increased in many little ways and we had everything to be well content with our lot.” M.W.S. Hitchcock remembered Gamble as “more remarkable as a housemaster than as a teacher, but at all times a great character”. A large man, with a rather severe countenance, he certainly commanded respect and boys knew better than to try disobey him. He would often appear, seemingly quite by chance, in the right place at the wrong time, as when he drove his car along a new bicycle track to find it blocked by a wall of snow carefully constructed by residents, and managed to feign mock surprise!

The housemaster’s wife still played an active role in catering and control of domestic staff at this time, and Mrs Gamble also supervised hand-washing, carried out ear inspections, and looked after boys in the sickroom. A pretty young matron, Miss Peto, much beloved by the boys, stood no nonsense and insisted on a daily dose of ‘radio malt’. The daily routine began with a maid ringing the getting up bell at 7am, closely followed at ten past by another bell which meant boys had to be in the showers. The 7.25 bell signalled breakfast in the hall at which boys sat on long benches. Lumpy porridge, and sometimes a cooked meal, would be supplemented with the residents’ own supply of cereal and jam. House assembly followed, with prayers and notices read by Mr Gamble. Lessons commenced at 9am, with dinner, the main meal of the day at 1pm with grace said beforehand. Organised games took place in the afternoons, sometimes more lessons, and high tea, prep and supper would end the day.

Free time was spent in the dining hall and adjacent reading room. OSH had inherited an extraordinary collection of nineteenth century books, including tales of African explorers, which kept the boys entertained. There was no wireless until 1935, but shortly before this one resident brought jazz records and a gramophone. On Saturday evenings Mr Gamble would let the boys listen to the popular In Town Tonightprogramme in his drawing room. On Sunday evenings there would be letter-writing in the hall and pocket money would be given out afterwards. Each year at the end of the summer term an OGs day was held when upper school boys returned to OSH for an afternoon of sports and tea with ice-cream. At the end of March 1936 it was announced in The Gresham that owing to the increase in numbers of boarders, OSH was to have a new wing built and would become a senior boarding house, with the juniors moving to Kenwyn.

The Senior House 1936-1993

Robert Lymbery, who was a boarder in OSH both as a junior and senior pupil, remembered the changes post 1936. This was a very different OSH, with no quad or Tin Tab, but a large extension along Church Street to accommodate studies, a new boot room, and entrance lobby. Assembly took place in Big School along with all classes and games. The new studies were used for prep and proved very popular. Other popular changes were that boys were allowed to listen to the radio and use their bikes on Sundays. Summing up, Lymbery says “The OSH was now really more of a dormitory and place for our private study and domestic affairs.”

Way out west

In June 1940 the decision was made to evacuate the entire School to Newquay for the duration of the War owing to fears of invasion. A goods truck in Station Yard was loaded with furniture and equipment, and three days later OSH was installed on the second floor of the Pentire Hotel. On the floor above, Farfield boys soon discovered the remnants of the hotel bar and set about finishing off its contents! Wind whistled through cracks in the old building, but the addition of electric fires made life more bearable for the residents. When not at lessons, boys were kept busy with surfing, swimming, beach soccer, tennis, rounders and golf. South Cornwall’s early new potatoes formed an important contribution to the nation’s food supplies, and boys often helped out at potato camps. M.W.S. Hitchcock made some observations on Newquay in general, remembering the pride he felt in still being part of his house and the excellent food including creamy milk and plentiful free-range eggs.

Arthur Gamble’s retirement notice outlined his many contributions to the School, but noted that “It was however in his House that he found his greatest joy, and there was able to exert his finest influence.” The new housemaster Eric Kelly was quietly spoken, unruffled, modest, with a dry sense of humour and a twinkle in his eye. A keen, gardener, he ensured that the house always had a supply of fresh vegetables. Prone to every cold, rather unfortunate in the somewhat Spartan conditions at Newquay, he was cruelly nicknamed ‘Drip’. It was Kelly’s job to rebuild the spirit of the house on the return from Newquay in 1944. The House Book tells us that numbers were rising and it was necessary to adopt a high table on a platform in the dining hall to accommodate them. A handicraft shed was opened with much help from ‘Jumbo’ Burrough, and gramophone recitals introduced on Sunday afternoons. Deep snow in 1947 saw residents busy tobogganing, skating and snowballing. Pits were dug for high and long jump on a corner of the playing field, and in the following year a house library was started and a billiards table acquired for the recreation room.

OSH in the 50s

In 1950 a mock election took place in the house library, when the Conservative candidate narrowly beat the Liberal representative. An OSH council was created in the hope of achieving greater cooperation through participation in the running of the house. Summer 1950 was the term of diseases, “the house has been shot through and spotted with quarantine and German Measles” reported the house captain. One popular suggestion was the purchase of a record player from HMV, a useful addition, particularly for the dance lessons led by Mr and Mrs Kelly and for music recitals. A new cycle track and hard tennis courts on the Eccles field helped keep OSH residents fit, as did a stealthy night-time expedition to Salthouse marshes by some senior boys. Success in the house cross country competition followed in 1956, and a house debating society and house orchestra provided further diversion. At the end of term Mr Kelly left for a retirement back in his native Australia after being presented with a silver salver by the boys of OSH.

New housemaster Paul Colombe, scholarly mathematician and wartime naval officer, was soon able to report that the house had shaken off some of its lethargy and was taking a renewed interest in house and school affairs. Unfortunately the handicraft shed was lost due to lack of enthusiasm, but the house musicians were still thriving, with a new music club and the only dance band in the school, the aptly namedGrasshoppers. OSH won the senior and junior rugby competition for the first time in 1956, and in 1958 the senior team won the house cricket for the first time since the War. In November 1958 OSH celebrated the centenary of its refounding in fine style with a formal supper complete with a talk on its history, toasts, anecdotes from housemasters, and an exhibition of old photographs and maps.

The swinging sixties

At the start of the 1960s the house captain was able to report that ‘a happy, contented atmosphere’ reigned in the house. A new interest was motor racing, and a club was formed with over half the residents as members. The club started by showing motor racing films but had great aspirations, and in a few years had developed into an engineering group with a workshop under the direction of tutor Dick Copas. In Lent 1965 it was reported with pride that “The old MG belonging to the House car club took to the road without even having to be pushed.” Boarding numbers in OSH were struggling, however, but a ‘grand clean up’ of discipline saw crime levels fall and behaviour improve. The house was also seen to be more cultured, winning the singing competition in 1961, forging ties with Runton Hill in a lacrosse match in 64, and attending dances at Hetheringsett and Norwich High School in 1965.

On occasion tensions with Holt youngsters would emerge, as in Lent term 1964 when “gentlemen of the town” reportedly ‘invaded’ the house. After an hour’s ‘relatively peaceful occupation’ of the senior corridor, though, the intruders decided to abandon their newly won territories and law and order was restored. Junior studies were improved and redecorated, whilst the prefects had a senior common room in the interests of promoting the cooperation necessary to run the house smoothly. The 60s were certainly a time of change for the house, with wins in cricket matches and renewed enthusiasm for athletics and swimming. James Dyson further inspired the house with his cross country coryphaena, leading in 1967 to a win in the senior house competition. By the early 70s the only group reported to be letting down the standards were the prefects, who had apparently been devoting a lot of their time to OSCAR, a dry white wine, orange or pineapple in flavour, brewed in the OSH common room!

The Corran years

Summer of 1971 saw a new housemaster, Peter Corran, who declared his intention to sweep away some cobwebs and create a happy atmosphere. It was a trying time, with low standards of behaviour and residents testing authority. House debates were re-introduced and proved highly successful, there were outings to plays such as Waiting for Godot at Sheringham, and tennis courts were built in place of the old walled garden. OSH was once again becoming more cultured with the help of tutor Richard Peaver, who produced the plays and coached the boys to win the house music competition in 1975. In an article recalling her days at OSH Angela Corran stressed the unique and special nature of the house, both in the sense of its history and its separate location from the rest of the School. She remembered rather a daunting task of taking it on in 1971, being faced with making 50 curtains in the days before moving in, before setting about running a house laundry, not to mention having to be adept at DIY and house maintenance.

Flu epidemics were another challenge and, on one occasion, with the San overflowing, up to 20 boys were in bed in the house, necessitating the constant ferrying of trays of food up and down the stairs. The house was a lively mixture of cultures, over half from Norfolk, and the rest made up of boys from the West Indies, Europe, Malaysia, America, Canada, Hong Kong and Iran. Boys brought some of their own culture to the mix, including food parcels at the start of term which were especially popular. Highlights included winning the house athletics, followed by hockey, cricket and rugby in the 70s, and of course the house plays which drew everyone together in a concerted effort. Peter Corran retired as housemaster in 1986, having been connected with the School since he joined as a thirteen-year old at Newquay in 1944.

The last years

OSH’s last chapter as a boarding house begins in 1986 with new housemaster Norman Semple and his wife Jan, and ends with its closure in 1993. Described as a “courageous and skilled” housemaster, Norman fulfilled his many duties with determination, energy and humour. Known for his diplomacy, he had a reputation for being kind, wise and approachable as a housemaster, and was determined to do his best for his house. The closure of OSH as a boarding house was a difficult and unpopular decision for headmaster John Arkell. Numbers had fallen by around 30 in the previous few years, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to persuade parents to board their sons in the town with the walk or cycle to Big School. Feelings ran high and parents sought a meeting with the chairman of the governors. As if in sympathy for the closure, the nearby 200 year old mulberry tree blew down in October 1992. Norman was determined to make the last years good ones for the house and maintained a positive outlook after the announcement was made. Fittingly, the boys of OSH won the house singing competition in their last year, 1993. Although many OGs were to mourn the loss of their beloved OSH, it was not long before the old place rose from mothballing to be reborn as the Pre-Prep School and once again echoed with the sound of joyful shouts and laughter. In May 2012 a reunion was held to celebrate 450 years in the life of the Old School House before another chapter in its life begins.

Some famous OSH OGs

Gerald Holtom (1924-31) Designer who was responsible for the logo for the newly formed Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1958 which became an international peace symbol. Won prizes for art at School and went on to study at the Royal College of Art.

Stephen Spender (1918-19) Poet Stephen Spender refers to all schools as prison camps in his autobiography World Within World, but admits that despite being homesick and unhappy at Gresham’s he did not want to leave. The sensitive youngster decided on a family holiday to the Lake District to become a poet, and after the early deaths of both parents, threw himself into writing in preparation for taking up a place at Oxford in 1927.

Richard Chopping (1928-35) Bond illustrator and artist Richard Chopping was encouraged to paint by his art teacher, and was already inspired by the natural world he later went on to illustrate so beautifully. In 1931 he contributed a poem Ode to a Dragonfly to the school’s literary magazine The Grasshopper. His artistic training began at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing and he was commissioned to illustrate a book on British butterflies. He is best known for designing six of the iconic covers of Ian Fleming’s James Bond books, including From Russia with Love(1957)

Leslie Everitt Baynes (1912-14) Pioneer aeronautical engineer. Early protagonist of the swing-wing principle and designer of flying boats for Short Brothers.

Sir James Dyson (1956-65) Inventor and businessman. Went on to study at the Royal College of Art before embarking on his career in engineering. He returned to Gresham’s on several occasions to inspire pupils with his story, readily acknowledging his debt to the School, in particular to the headmaster for providing the financial assistance to allow him to continue his education following the death of his father. In 1978 he began work on the dual cyclone vacuum cleaner, first marketed in Japan, now a market leader sold worldwide, which was to make him a household name. In 2002 he established the Dyson Foundation which supports a range of educational, medical and scientific charities, and in 2007 he received a knighthood.